Lessons from 15 years living with my code

Musings from a long-timer, about to become a newbie

At the time of writing, I am about to change jobs after over 15 years in my current role. This, I suspect, is quite unusual for the IT business. Given this, here are some thoughts on my experience of writing software and then having to be responsible for it for a long, long time.

Log, log, and log some more

One lesson from supporting the same software for over a decade is that quality logging will be your friend. In my time, I inherited more than one area of tooling where logging was almost non-existent. The consequences of which were that delivery using that tooling was difficult and error prone. When redeveloping these areas, I made a point of ensuring that the tools explained what they were doing at varying levels of detail. By using logging frameworks, these levels could be switched on or off. For production, there would be minimal logging for reasons of speed. For development, full disclosure to give a detailed view into why a certain result occurred. The key was to treat the logging as an integral part of the overall product and not as an afterthought.

Where individual services were developed, I paid attention to ensuring that logging occurred at the service boundary. That all inbound calls could be logged along with the overall success or failure of the call. I developed standard components to make this as simple and consistent as possible. The result was that it was always straightforward to see if an error was emanating from a service that I was responsible for and where that error had occurred. I was always surprised to see how many services had no such blame deflection capability.

Pay attention to errors

Paying attention to errors most definitely paid dividends over the years. My experience is that people rarely come round to tell you that your component is working flawlessly, they are much more likely to come round when something has gone wrong. By paying attention to errors, I am talking about both throwing meaningful errors and handling them effectively too.

For me, a meaningful error is one that has a well-worded message and contains as much key information as is feasible at the point it is raised. For example, 'Unexpected input' or 'Error 4235' are not what I would consider well-worded. If viewed in isolation, which errors often can be, they are meaningless. The mindset I would suggest, is to put yourself in the position where all you have to work with is the message. Another tip here is to always have static text at the start of the message, to make it easier to locate in a codebase.

When it comes to handling errors, my experience is that unless you can add value then you do nothing. To often I have seen errors being handled such that vital information being lost. A classic C# mistake is to throw ex and throw away the stack trace in the process. You need to understand how errors bubble up in your chosen tech. My approach was to test that any errors raised manifested themselves in a meaningful way, either in a response or a log. The result was that when these occurred in the wild, and I was dragged into help, I had clear clues to guide me. Don't leave yourself in the dark.

BYOM - Bring Your Own Model

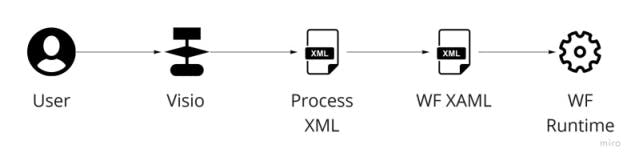

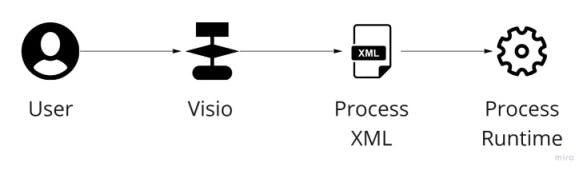

One of the projects I was tasked with was to create a process orchestration framework with a visual editor. The framework was to use Windows Workflow Foundation v1 and the editor to use Visio 2007 as an embedded control. Workflows in Workflow Foundation were defined by a XAML file, so the task could be solved by building a UI that walked the nodes in the Visio diagram object model and outputted the appropriate XAML for the runtime. However, I decided to bring my own process model to the party.

What were my reasons for doing so?

- To isolate the editor from runtime. I didn't want the Windows Form editor to have references to the Workflow Foundation components. With an intermediate model this could be avoided.

- Workflow Foundation XAML V1 was a pure hierarchical model, so required some complex generation to model non-hierarchical processes.

- Workflow Foundation XAML was V1 and so was a prime candidate to change (and it did!)

What we found when we started to use it in anger was that Workflow Foundation V1 was slow and that is had a threading model not compatible with our components. The solution? Write our own process runtime using, you guessed it, our own model.

Owning your model gives you a degree of independence. There is a good argument that you ain't going to need it, that it adds a level of unnecessary indirection. You will need to balance this against the advantages. I found that having your own model makes you really think about what you need in it and what you don't. The upshot being a deeper understanding of the domain you are dealing with.

BTW Eventually we got rid of Visio too, replacing it with - no surprise - our own lightweight, custom-for-purpose model.

KISS - Keep It Simple Stupid

For one project, we had to build a back-end service that received files and queued them up to be spooled to the printer. I was under pressure from a senior member of staff to use a relational database as an index for the jobs. In the end I went with the simplest solution I could think of, and made it all file-based. The result, simple to deploy and maintain. Need to retry a job? Drag it from the failure folder to the input folder. Need to test the printing? Drop a file into the input folder. Simplicity really does help in the long run, especially if you have to support it.

This goes for algorithms, regular expressions, and data structures too. If you are going to be coming back to software you haven't seen for 5 years, you want to make it easy for yourself (not to mention others).

Embrace testing

In my 15 years, one of the changes I made was to understand and embrace testing. This was primarily unit testing, with attention being paid to how to create meaningful tests that were neither brittle nor flaky. Roy Osherove's book The Art of Unit Testing was a particular inspiration, making me think deeply about how to do this. Some of the tests I wrote were 'classic' unit tests and some were snapshot tests (also known as approval tests).

For the core infrastructure that I built and supported, I paid close attention to unit testing possible error conditions and ensuring that they were reported in a meaningful way. This could actually form the bulk of the testing, as things have many more ways to fail than succeed. However, this thoroughness paid dividends in support, allowing me to quickly understand the underlying cause of issues.

'A bug is a test that has yet to be written' quipped someone wiser than myself. I took this on board, and tried to be rigorous in creating a test to recreate an issue before diving into the code to fix it. Sometimes this is tempting as you get that feeling that you know exactly what needs to be fixed. However, sometimes you are wrong. Yes, even you. I found that taking the time to fashion a test recreating the issue often yields insights that you would never get from just patching the code.

Attention to clean code really does make a difference

No surprises here, but thoughtful naming, reasonable method size, and all the other factors that result in clean code make a huge difference in the long run. I was always happy to return to my own code, not because it was cleverer than anyone else's, but because I always paid attention to those principles as best I could. I tried to never let my standards drop and I was always very grateful for that on my return. Code is read many, many more times than it is written. Especially over the course of 15 years.