Recently, my focus at work has shifted from AWS development to Azure development. To help myself get properly acquainted with the technology, I have decided to set myself a Azure-based serverless challenge. That is, to build a multi-tenant webhook proxy. First using ClickOps and then using Infrastructure as Code (IaC). In this post, I will first look at writing a single Azure Function and see what that brings.

The Webhook Proxy Application

The ultimate goal is to create a serverless application that can be placed in front of internal systems to robustly handle webhook callbacks. Its functionality will cover:

- Validating the content of the callback

- Storing the content of the callback

- Forwarding the content to a downstream system

- Automatically retrying if the downstream system is offline

- Forwarding to a dead letter queue if not able to forward

In AWS, I would probably build the application using API Gateway calling a Lambda function, that stored the request in S3. Then handle the S3 events raised, using a combination of Lambda functions and Event Bridge to deliver the request.

The appealing aspect of this task is that it is a real-world need, and that it covers API management, functions as a service, serverless storage, and events. This means I will need to tangle with the following Azure technologies:

My first step on this journey is to create, test, and deploy an Azure Function that validates the contents of an HTTP according to a schema specified as part of the path.

Choosing an Azure Function model

Things rarely turn out to be as straightforward as you think, and straight away I was forced to make a choice as to the Azure Function model to use. Since I last explored them, there is a new 'isolated worker model' for running Azure Functions. The Microsoft article on the differences between the isolated worker model and the in-process model explains that there are two execution models for .NET functions:

Execution model Description Isolated worker model Your function code runs in a separate .NET worker process. Use with supported versions of .NET and .NET Framework. In-process model Your function code runs in the same process as the Functions host process. Supports only Long Term Support (LTS) versions of .NET.

The Guide for running C# Azure Functions in an isolated worker process explains the benefits for the newer model:

- Fewer conflicts: Because your functions run in a separate process, assemblies used in your app don't conflict with different versions of the same assemblies used by the host process.

- Full control of the process: You control the start-up of the app, which means that you can manage the configurations used and the middleware started.

- Standard dependency injection: Because you have full control of the process, you can use current .NET behaviors for dependency injection and incorporating middleware into your function app.

In my experience, when Microsoft develop a new model then it is better to adopt it if you can. The older models do not seem to get quite the same love. So given that, it was the isolated worker model for me.

The 'Out of the Box' Experience

The Microsoft article Create your first C# function in Azure using Visual Studio was my guide to getting started. The experience compared to Lambda functions in AWS is quite stark. Visual Studio is a one-stop development environment for .NET, whereas AWS and VS Code feels like an 'assemble your own' adventure.

As long as you remember to select the Azure development workload during installation of Visual Studio, then it only took a few steps after selecting the 'Azure Functions` template before I could hit F5 and have the following code executing:

[Function("HttpExample")]

public IActionResult Run(

[HttpTrigger(AuthorizationLevel.Anonymous, "get", "post")] HttpRequest req)

{

return new OkObjectResult("Welcome to Azure Functions!");

}

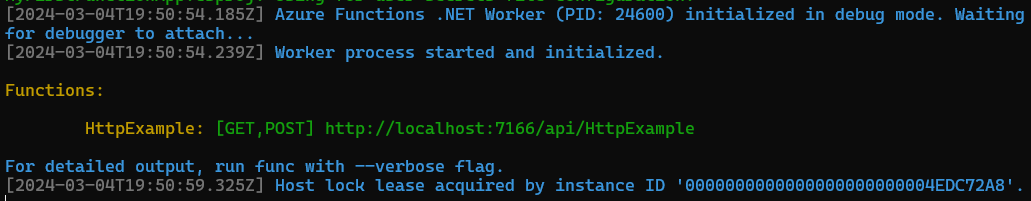

Visual Studio had seamlessly started a local hosting process at http://localhost:7166/api/HttpExample, as can be seen below:

So straight away, I could set break points and benefit from a super-quick inner development loop. However, it turned out that the generated code was not the only way to go.

The Built-in HTTP model

As the HTTP trigger documentation states:

HTTP triggers allow a function to be invoked by an HTTP request. There are two different approaches that can be used:

I consulted with ChatGPT, which had the opinion:

The choice between the built-in Azure Functions HTTP trigger model and ASP.NET Core integration depends on the complexity of your application, the need for control over the HTTP pipeline, and your familiarity with ASP.NET Core. For simpler, serverless applications, the built-in model is often the best choice due to its simplicity and tight integration with Azure. For more complex applications requiring the full feature set of ASP.NET Core, integrating with ASP.NET Core would be more appropriate.

Probing ChatGPT a bit more as to the limitations of the Built-in HTTP model, I got the following scenario where the more complex model might be needed:

While the built-in model of Azure Functions is powerful for many use cases, especially those that fit well within a serverless paradigm, it has its limitations in scenarios requiring advanced control over HTTP pipeline processing, complex authentication and authorization, and other sophisticated web API features. In these cases, integrating with a more feature-rich framework like ASP.NET Core would be more appropriate.

Given that I intend to front the function with Azure API Management to handle the authorisation aspects, I decided to go with the simplicity of the built-in model. This meant that the original boilerplate code became the following:

[Function("HttpExample")]

public HttpResponseData Run(

[HttpTrigger(AuthorizationLevel.Anonymous, "get")] HttpRequestData req)

{

var response = req.CreateResponse(HttpStatusCode.OK);

response.WriteString("Welcome to Azure Functions!");

return response;

}

So a little more verbose, but I could get rid of a dependency which was nice. I did have to amend Program.cs to use the defaults for a worker process:

var host = new HostBuilder()

// Was ConfigureFunctionsWebApplication()

.ConfigureFunctionsWorkerDefaults()

.Build();

Dependency Injection and Logging

One significant difference that struck me between AWS Lambda functions and Azure Functions, was that the latter starts you off down the dependency injection (DI) route. The boilerplate code uses DI out of the box to inject an ILoggerFactory implementation that can then be used to obtain a logger:

public class SimpleHttpFunction(ILoggerFactory loggerFactory)

{

private readonly ILogger _logger =

loggerFactory.CreateLogger<SimpleHttpFunction>();

[Function("HttpExample")]

public HttpResponseData Run(

[HttpTrigger(AuthorizationLevel.Anonymous, "get")] HttpRequestData req)

{

_logger.LogInformation("C# HTTP trigger function processed a request.");

As with a 'normal' application, the logging level is controlled within the Program.cs file. Here I want to have a very verbose output in development, but leave the level when in higher environments.

var host = new HostBuilder()

// ...

.ConfigureLogging((context, loggingConfig) =>

{

var env = context.HostingEnvironment;

if (env.IsDevelopment())

loggingConfig.SetMinimumLevel(LogLevel.Trace);

})

// ...

.Build();

I decided to take advantage of the dependency injection and adopt a little hexagonal architecture. I created a couple of services to isolate my function from the details of how a request is validated and how the request content is stored.

var host = new HostBuilder()

// ...

.ConfigureServices(services =>

{

services.AddSingleton<IRequestValidator, RequestValidator>();

services.AddSingleton<IRequestStore, BlobRequestStore>();

})

.Build();

With this in place, I could then use a primary constructor to have the implementations injected at runtime. This would also set me nicely to do some unit testing later on.

public class ValidateAndStoreFunction(

ILoggerFactory loggerFactory,

IRequestValidator requestValidator,

IRequestStore requestStore)

{

private readonly ILogger _logger =

loggerFactory.CreateLogger<ValidateAndStoreFunction>();

private readonly IRequestValidator _requestValidator = requestValidator;

private readonly IRequestStore _requestStore = requestStore;

As mentioned earlier, this all feels quite different to working with AWS Lambda functions. In AWS, it felt like the onus was on keeping everything as light as possible. I have never used any dependency injection frameworks with AWS, so this felt much more like 'normal' application development. My concern, as with all serverless functions, was that this would add to any cold start times. However, for my learning application, I am not too concerned. For those that are, Mikhail Shilkov has written this excellent article on Cold Starts in Azure Functions.

Unit testing my function

Whilst it was great to be able to run my function and invoke it from cURL or Postman, I like to write pure unit tests that can be run from anywhere. This turned out to be quite straightforward, at least in the case of my function.

The first task was to instantiate and instance of ValidateAndStoreFunction. The primary constructor for this is as follows:

ValidateAndStoreFunction(

ILoggerFactory loggerFactory,

IRequestValidator requestValidator,

IRequestStore requestStore)

Using the Moq mocking framework, I was able to supply mocks for these and setup appropriate return values.

_mockLoggerFactory = new Mock<ILoggerFactory>();

_mockRequestValidator = new Mock<IRequestValidator>();

_mockRequestStore = new Mock<IRequestStore>();

The first real snag was the signature of the Run method. It requires a HttpRequestData as input:

HttpResponseData Run(

HttpRequestData req,

string contractId,

string senderId,

string tenantId)

It turns out that HttpRequestData is an abstract class, so I tried to subclass it. This hit a couple of issues. The first was that HttpRequestData has a constructor that requires a FunctionContext instance. FunctionContext is itself abstract, so I tried using Moq to provide one.

class MockHttpRequestData()

: HttpRequestData(new Mock<FunctionContext>().Object)

HttpRequestData also need to be able to create an HttpResponseData instance. The solution, again I subclassed HttpResponseData and return an instance of my new class.

public override HttpResponseData CreateResponse() => new MockHttpResponseData();

The final step was to be able to pass in an object to be returned as a JSON stream.

class MockHttpRequestData(object bodyObject)

: HttpRequestData(new Mock<FunctionContext>().Object)

{

private readonly string _bodyJson = JsonConvert.SerializeObject(bodyObject);

public override Stream Body => GetStringAsStream(_bodyJson);

Now with my mocks in place, I could create some nice simple unit tests that would run anywhere.

// Arrange

var validateAndStoreSUT = new ValidateAndStoreFunction(

_mockLoggerFactory.Object, _mockRequestValidator.Object, mockRequestStore.Object);

// Act

var response =

validateAndStoreSUT.Run(

new MockHttpRequestData(

new { }), ExpectedContractId, ExpectedSenderId, ExpectedTenantId);

// Assert

response.Should().NotBeNull();

response.StatusCode.Should().Be(HttpStatusCode.Created);

I don't know if other trigger would be more difficult to mock out, but the ease of mocking HttpRequestData gives me cause for optimism.

Deploying to Azure

My original intention was to finish this post with deploying to Azure from Visual Studio. However, this did not prove as straightforward as thought and I will defer the trials and tribulations to the next post.

Summary

Here are my observations on my first real experience with Azure Functions:

Azure Functions feel more like a traditional application than AWS Lambda functions. With dependency injection and a local development experience.

The two available models, in-process and isolated, complicates initial decisions.

Strong support for the local (F5) experience. This makes it easy to get going and there is support for remote debugging too that I didn't have time to investigate.

The middleware limitations stopped me in my tracks. I was hoping to be able to extend my functions with middleware that would short-circuit the pipeline, but this turned out not to be possible.

Unit testing was straightforward, with support for dependency injection and the framework classes making it easy to mock the inputs to the function.