Designing a CDK State Machine Builder - Part 1

API-first component development

In my previous previous post, I was a little critical of the CDK approach to defining state machines. In this post, I attempt to design an alternative and share my approach to developing such an API. Whether the result is better or worse than the original, that is up to you.

The code for this post can be found on GitHub here.

Edit: The resulting code is now available as an npm package.

My main criticism of the CDK approach is as follows:

- Readability

- Maintainability

- Interaction with Prettier

Let us take a simple example where we have a state machine consisting of six states in series. Using the CDK approach, we would chain the states together as follows:

const definition = sfn.Chain.start(

state1.next(state2.next(state3.next(state4.next(state5.next(state6)))))

);

For me, it doesn't score highly on the readability front. The syntax highlighting helps pick out the states, but the required nesting and resulting accumulation of brackets jars my eye. On maintainability, adding another state wouldn't be too bad, but it may not jump out in the pull request. As for Prettier, it doesn't have much to say in this example.

Being a critic is easy, but having a go yourself is another thing. The way I like to start is to just write the code as I would ideally like to express the problem. In this case, I have experimented in the problem area before and had the Fluent Builder Pattern as a possible solution. With this in mind, I wrote the following code:

const definition = new StateMachineBuilder()

.perform(state1)

.perform(state2)

.perform(state3)

.perform(state4)

.perform(state5)

.perform(state6)

.build();

The idea here is that we add states sequentially to the instantiated StateMachineBuilder, and when complete we call the build method to return a definition. The advantage is that we can easily see the states and their order, we can easily reorder them, and that Prettier will format nicely for us.

To get the code to compile, I created a skeleton implementation for StateMachineBuilder.

export default class StateMachineBuilder {

perform(state: sfn.State): StateMachineBuilder {

return this;

}

build(): sfn.IChainable {

throw new Error('build not implemented yet');

}

}

At this moment of the development, I was not overly concerned about fleshing out the implementation. For me, the danger of doing adding implementation at this stage is that you make it harder for you to rework the API as you explore the problem space. This runs the risk of tying yourself into abstractions and syntax that you have to live with forever, and that may well have benefitted from refinement.

At this stage, I was content if I can envisage how the implementation would work. In this case, I envisaged the StateMachineBuilder accumulating the states, and then wiring them up when build is called. Given this, I was happy to proceed to the next example, choices.

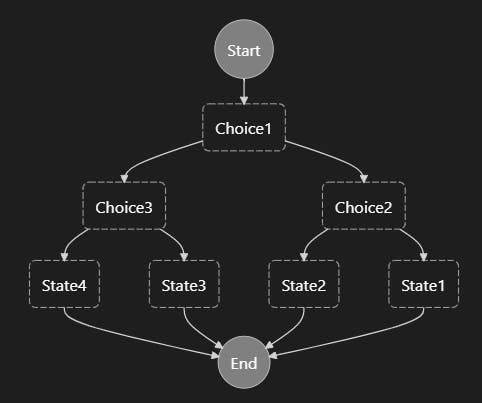

For this, I created a CDK definition for the following flow:

The result was as follows:

const definition = sfn.Chain.start(

new sfn.Choice(definitionScope, 'Choice1')

.when(

sfn.Condition.booleanEquals('$.var1', true),

new sfn.Choice(definitionScope, 'Choice2')

.when(sfn.Condition.booleanEquals('$.var2', true), state1)

.otherwise(state2)

)

.otherwise(

new sfn.Choice(definitionScope, 'Choice3')

.when(sfn.Condition.booleanEquals('$.var2', true), state3)

.otherwise(state4)

)

);

On the readability front, I found the distance between the when and otherwise for Choice1 to be less than ideal. However, at least Prettier had done a decent job with providing meaningful indentation in this case.

Using the fluent builder approach, I played around with various syntaxes and settled on the following approach:

const definition = new StateMachineBuilder()

.choice('Choice1', {

choices: [{ when: sfn.Condition.booleanEquals('$.var1', true), next: 'Choice2' }],

otherwise: 'Choice3',

})

.choice('Choice2', {

choices: [{ when: sfn.Condition.booleanEquals('$.var2', true), next: 'State1' }],

otherwise: 'State2',

})

.choice('Choice3', {

choices: [{ when: sfn.Condition.booleanEquals('$.var3', true), next: 'State3' }],

otherwise: 'State4',

})

.perform(state1)

.end()

.perform(state2)

.end()

.perform(state3)

.end()

.perform(state4)

.end()

.build(definitionScope);

The first big choice (no pun intended) was to have the builder instantiate the Choice objects itself. A knock-on effect of this, is that the build method now needs to take the scope under which the Choice objects are created. This does have the benefit of not having to specify the scope with every choice.

The next choice was how to do the branching. In contrast to the CDK approach, I decided on using references to the id values of the states. Whilst this could lead to errors, I could envisage the build method doing validation and picking these up. Given this, I was happy to go with this approach, as it avoids the problem of ever-increasing indentation as the branches get more and more nested.

I originally went with the approach that the choice would drop through to the next step in the flow. However, after experimenting with writing a few mock examples, I felt that having an explicit otherwise made the code more readable, whilst also having the benefit of matching the terminology of CDK. This reworking was very straightforward, as I had yet to write any implementation. All I needed to write, was just enough code to make the examples compile.

To facilitate this, I needed to extend the CDK ChoiceProps to allow the choice to be defined with the core CDK properties, along with an array of choices and the alternative.

interface BuilderChoice {

when: sfn.Condition;

next: string;

}

interface BuilderChoiceProps extends sfn.ChoiceProps {

choices: BuilderChoice[];

otherwise: string;

}

This example brought to light the need for an end method. This indicates to the StateMachineBuilder that the previous state is a terminal one.

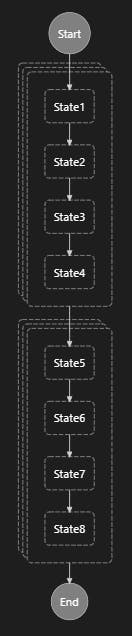

Another state machine control structure is the Map state. This state selects an array of items from the input and invokes an inner state machine for each item. I considered the following example, where two Map states each invokes inner state machines with four sequential steps.

Using raw CDK, this is defined as:

const definition = sfn.Chain.start(

new sfn.Map(definitionScope, 'Map1', {

itemsPath: '$.Items1',

})

.iterator(state1.next(state2.next(state3.next(state4))))

.next(

new sfn.Map(definitionScope, 'Map2', {

itemsPath: '$.Items2',

}).iterator(state5.next(state6.next(state7.next(state8))))

)

);

In this case, I felt that Prettier was not helping and the result was difficult to read. For me, it was hard to see that the iterator was part of the Map, and that there were two Map states chained together.

A bit of experimentation with various syntaxes later, I settled on defining this scenario as follows:

const definition = new StateMachineBuilder()

.map('Map1', {

itemsPath: '$.Items1',

iterator: new StateMachineBuilder()

.perform(state1)

.perform(state2)

.perform(state3)

.perform(state4),

})

.map('Map2', {

itemsPath: '$.Items2',

iterator: new StateMachineBuilder()

.perform(state5)

.perform(state6)

.perform(state7)

.perform(state8),

})

.build(definitionScope);

In this case, Prettier has done a splendid job for us and, IMHO, it is very clear as to what is going on. If we needed to reorder the steps, then that would be very straightforward indeed. The key to this was supplying the map method with a BuilderMapProps instance.

interface BuilderMapProps extends sfn.MapProps {

iterator: StateMachineBuilder;

}

The question that I had to consider was whether I could make the implementation work. I could envisage the outer build method traversing the states and, for Map states, invoking the build method on any iterator values with the scope passed to it. This would give us the definition to supply to the CDK iterator method. Confident this would probably work, I moved onto how to implement Parallel states.

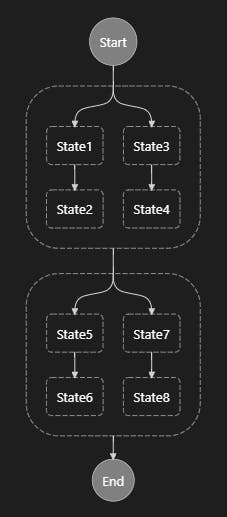

One of the very nice features of step functions is that you can easily set up tasks to be performed in parallel, with the infrastructure taking care of the heavy lifting for you. Consider the following state machine, where we have two Parallel states that each have two branches to be executed in parallel.

In CDK, and formatted by Prettier, the resulting definition is as follows:

const definition = sfn.Chain.start(

new sfn.Parallel(definitionScope, 'Parallel1')

.branch(state1.next(state2))

.branch(state3.next(state4))

.next(

new sfn.Parallel(definitionScope, 'Parallel2')

.branch(state5.next(state6))

.branch(state7.next(state8))

)

);

As with the Map example, Prettier doesn't do a great job with readability. For the syntax, I took inspiration from the approach for map and came up with the following.

const definition = new StateMachineBuilder()

.parallel('Parallel1', {

branches: [

new StateMachineBuilder().perform(state1).perform(state2),

new StateMachineBuilder().perform(state3).perform(state4),

],

})

.parallel('Parallel2', {

branches: [

new StateMachineBuilder().perform(state5).perform(state6),

new StateMachineBuilder().perform(state7).perform(state8),

],

})

.build(definitionScope);

This approach resulted in the branches being clearly nested within the parent parallel methods. As with map, I needed to provide an extended properties instance to define them.

interface BuilderParallelProps extends sfn.ParallelProps {

branches: StateMachineBuilder[];

}

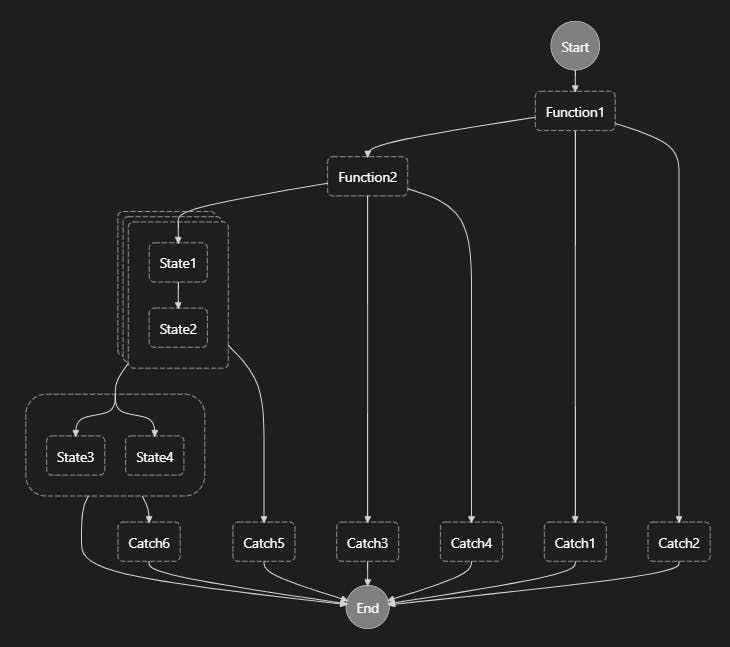

The final step function control structure to tackle was catch blocks. These allow errors generated by states to be caught, and then the flow of the state machine routed to recovery processing. Consider the following flow where the all the states have catch blocks to recover from a variety of errors.

This is expressed in CDK as follows:

const definition = sfn.Chain.start(

function1

.addCatch(catch1, { errors: ['States.Timeout'] })

.addCatch(catch2, { errors: ['States.All'] })

.next(

function2

.addCatch(catch3, { errors: ['States.Timeout'] })

.addCatch(catch4, { errors: ['States.All'] })

.next(

new sfn.Map(definitionScope, 'Map1', {

itemsPath: '$.Items1',

})

.iterator(state1.next(state2))

.addCatch(catch5)

.next(

new sfn.Parallel(definitionScope, 'Parallel1')

.branch(state3, state4)

.addCatch(catch6)

)

)

)

);

As with some of the other examples, I felt that Prettier had resulted in the essence of the flow being lost. It certainly wasn't clear to me that, at the top level, there were four sequential states, each with error handlers. I imagined trying to re-order them and hoping to get the brackets right.

It made sense to me to have the handlers as properties of the state. With this in mind, I created BuilderCatchProps and added it to the properties for the perform, map, and parallel methods.

interface BuilderCatchProps extends sfn.CatchProps {

handler: string;

}

interface BuilderPerformProps {

catches?: BuilderCatchProps[];

}

interface BuilderParallelProps extends sfn.ParallelProps {

branches: StateMachineBuilder[];

catches?: BuilderCatchProps[];

}

interface BuilderMapProps extends sfn.MapProps {

iterator: StateMachineBuilder;

catches?: BuilderCatchProps[];

}

Now we could rewrite the CDK version as the following.

const definition = new StateMachineBuilder()

.perform(function1, {

catches: [

{ errors: ['States.Timeout'], handler: 'Catch1' },

{ errors: ['States.All'], handler: 'Catch2' },

],

})

.perform(function2, {

catches: [

{ errors: ['States.Timeout'], handler: 'Catch3' },

{ errors: ['States.All'], handler: 'Catch4' },

],

})

.map('Map1', {

iterator: new StateMachineBuilder().perform(state1).perform(state2),

catches: [{ handler: 'Catch5' }],

})

.parallel('Parallel1', {

branches: [

new StateMachineBuilder().perform(state3),

new StateMachineBuilder().perform(state4),

],

catches: [{ handler: 'Catch6' }],

})

.end()

.perform(catch1)

.end()

.perform(catch2)

.end()

.perform(catch3)

.end()

.perform(catch4)

.end()

.perform(catch5)

.end()

.perform(catch6)

.end()

.build(definitionScope);

Whilst the definition is considerably lengthier than the CDK version, I felt that the essence of the flow was well-separated from the exception handling. It also led me to consider a performAndEnd method, with the aim of making the definition a bit briefer. However, at this stage I felt that keeping the syntax simple was the way to go.

At this point, I had an alternative way of defining state machines in CDK. At least in theory. It is more verbose, that is for sure, but - IMHO - it is more readable, more maintainable, and plays nicer with Prettier. This API was developed with the implementation in mind, but without committing to one. This allowed me to iterate very quickly over different ways of expressing the problem with code, until I found one that I felt was as good as I could make it.

In the next post, we shall see how I get on with implementing the theory.

Edit: The resulting StateMachineBuilder component is now available on npm.