In the previous parts in the series, I explored how we can leverage CDK to construct serverless applications out of components that can be individually deployed and tested in the cloud. In this part, I look at how we can treat step functions in a similar way, and how we can add a mocking capability to the testing components to make this easier.

AWS describe step functions as follows:

AWS Step Functions is a low-code visual workflow service used to orchestrate AWS services, automate business processes, and build serverless applications. Workflows manage failures, retries, parallelization, service integrations, and observability so developers can focus on higher-value business logic.

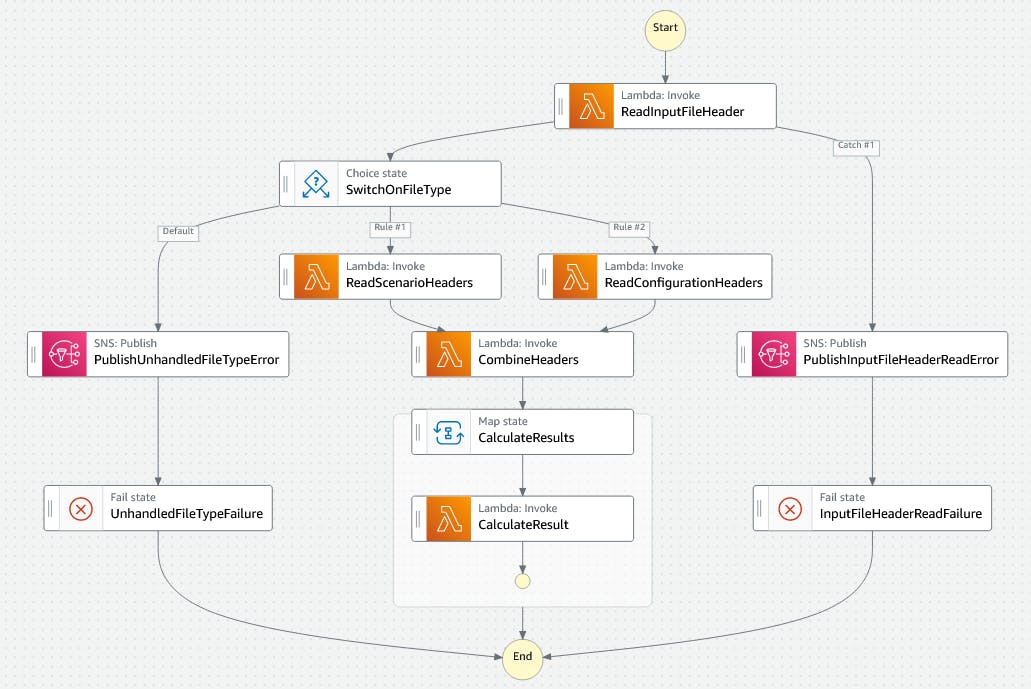

The State Machine

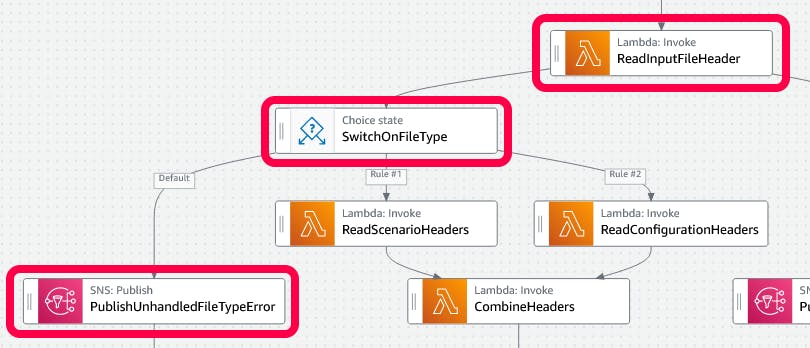

Let us get straight to it and look at the workflow that we wish to test, as rendered by the brand new Workflow Studio.

This part of the application is concerned with combining affordability configurations, e.g. use 3 time basic salary, with affordability scenarios, e.g. basic salary of £40K. It then calculates, or recalculates, the result.

One happy path goes something like this:

- A file change event triggers the step function.

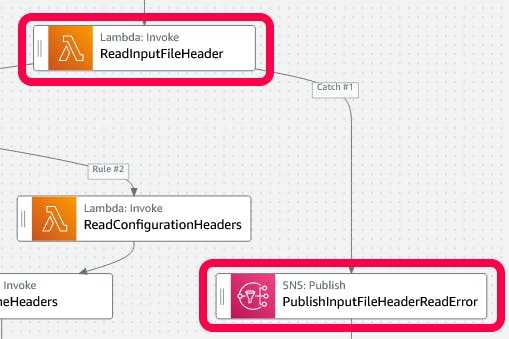

- The ReadInputFileHeader lambda loads the file from S3 and extracts the file header.

- The SwitchOnFileType choice looks at the file header type and sees

Configuration. - The ReadScenarioHeaders lambda loads all Scenario headers.

- The CombineHeaders lambda outputs an array of all Configuration and Scenario tuples.

- The CalculateResults map iterates over the array of Configuration and Scenario tuples

- For each Configuration and Scenario tuple, the CalculateResult lambda calculates the result and stores it in S3.

In addition, there are two unhappy paths. One where the initial read fails (after a maximum of 2 retries), and another where the file type is neither Configuration or Scenario.

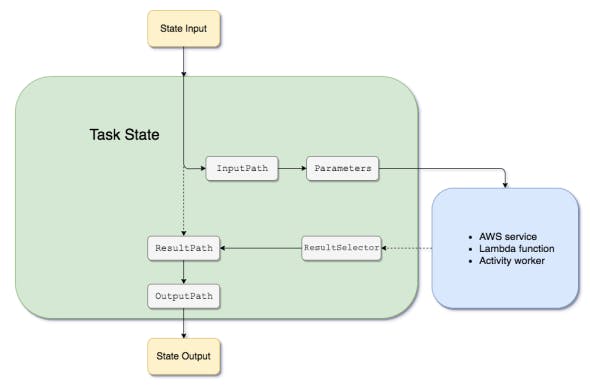

The Testing Challenge

In my experience, one of the challenges of step function development is getting the input and output processing right. The following diagram is from the AWS documentation and shows that the process has quite a few moving parts.

In fact, AWS have a tool just for debugging this process called the Data flow simulator.

IMHO, having to provide such a tool indicates that approach taken to state management may not be as intuitive as it could have been.

Given this, one challenge is how to test these mappings. That is, how do you test that the data flows through the step function as expected.

Another challenge is how to to test another key feature of step functions, error handling. Step functions are great in that you can define retry policies and error handlers, thereby making your processing more robust. The trick is how do you test that when these conditions arise, the step function behaves as you expect.

The Testing Approach

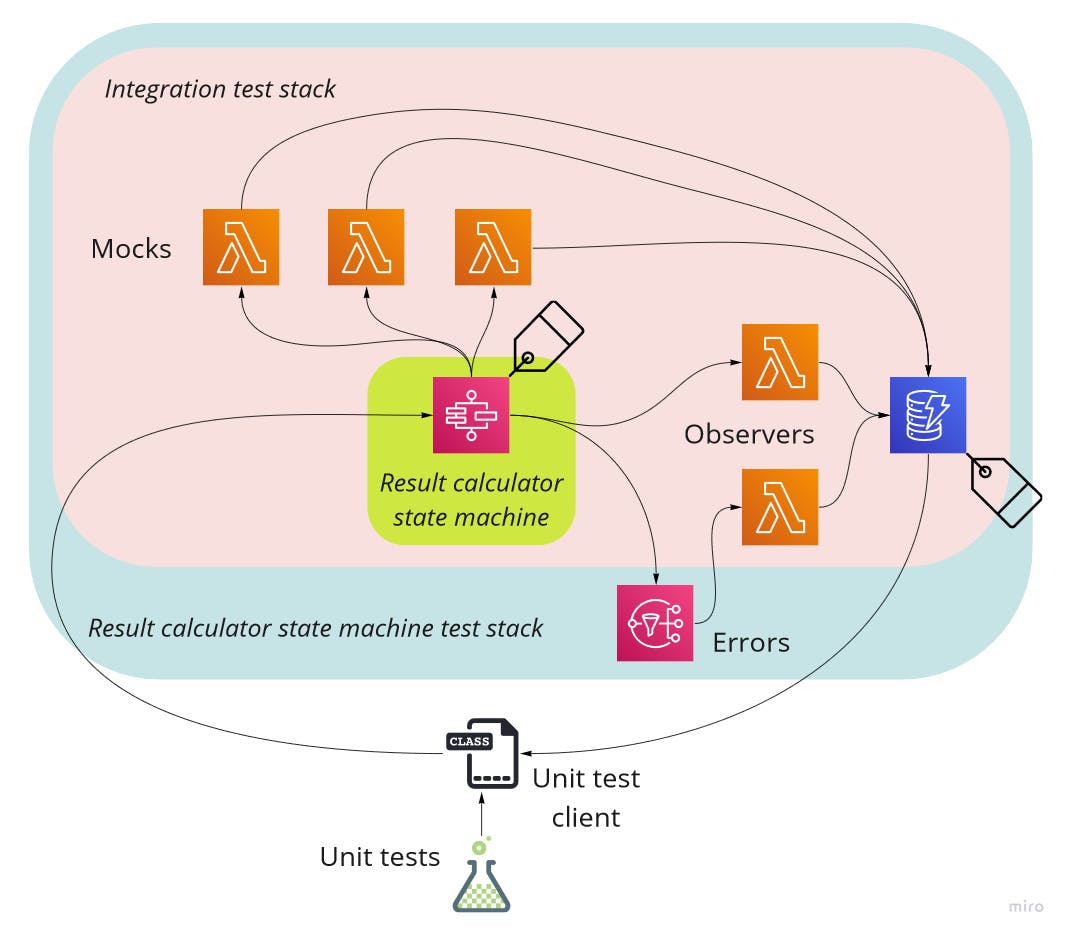

The approach I am going to take here is to concentrate on testing the flow and mappings of the step function. I am going to assume that the lambda functions adhere to known contracts and wire the step function to mock and observer versions of those functions. These versions will be provided by the testing infrastructure. The resulting test architecture looks like the following.

As you will see further on, for each test, the mock functions are given an array of expectations and responses. These are asserted and replayed respectively. In addition, a mock function can be made to error and this allows us to test the error handling scenarios. On the other hand, observer functions simply write the received event to a table for later assertion by the unit test.

The Testing Constructs

The System Under Test

The first construct to create is the step function. Since we want the functions and the topic to be passed in for testing purposes, we need to follow the CDK pattern and create a Props interface along with our subclass of StateMachine.

export interface ResultCalculatorStateMachineProps

extends Omit<sfn.StateMachineProps, 'definition'> {

fileHeaderReaderFunction: lambda.IFunction;

fileHeaderIndexReaderFunction: lambda.IFunction;

combineHeadersFunction: lambda.IFunction;

calculateResultFunction: lambda.IFunction;

errorTopic: sns.ITopic;

}

export default class ResultCalculatorStateMachine extends sfn.StateMachine {

constructor(scope: cdk.Construct, id: string, props: ResultCalculatorStateMachineProps) {

super(scope, id, {

...props,

definition:

StateMachineBuilder.new()

// ...snip...

});

}

}

The code for the full definition can be found on the GitHub repo here.

Note that I use my own State Machine Builder npm package. I don't like the AWS fluent interface, so I built my own using the builder pattern (🎺 <- my own trumpet being blown 😊). I also blogged about it here.

The Testing Stack

Now we have our step function, we can host it in a testing stack. In the last part, we started using a base stack with reusable functionality, like the ability to tag resources for easy location and the ability to deploy observer functions. In this part, we continue this process, taking advantage of functionality to deploy mocks as well as observers.

We start by sub-classing IntegrationTestStack, to get access to all the functionality within it.

export default class ResultCalculatorStateMachineTestStack extends IntegrationTestStack {

Next we declare a set of static values that will be used by the unit tests to locate resources, define mock responses, and retrieve observations.

static readonly ResourceTagKey = 'ResultCalculatorStateMachineTestStack';

static readonly StateMachineId = 'ResultCalculatorStateMachine';

static readonly FileHeaderReaderMockId = 'FileHeaderReaderMock';

static readonly FileHeaderIndexReaderMockId = 'FileHeaderIndexReaderMock';

static readonly CombineHeadersMockId = 'CombineHeadersMock';

static readonly ResultCalculatorObserverId = 'ResultCalculatorObserver';

static readonly ErrorTopicObserverId = 'ErrorTopicObserver';

The observers and mocks are defined simply by specifying values for observerFunctionIds and mockFunctionIds in the stack properties.

super(scope, id, {

testResourceTagKey: ResultCalculatorStateMachineTestStack.ResourceTagKey,

observerFunctionIds: [

ResultCalculatorStateMachineTestStack.ResultCalculatorObserverId,

ResultCalculatorStateMachineTestStack.ErrorTopicObserverId,

],

mockFunctionIds: [

ResultCalculatorStateMachineTestStack.FileHeaderReaderMockId,

ResultCalculatorStateMachineTestStack.FileHeaderIndexReaderMockId,

ResultCalculatorStateMachineTestStack.CombineHeadersMockId,

],

});

Behind the scenes, IntegrationTestStack will deploy observer and mock functions configured with the ids specified. IntegrationTestStack will also deploy a DynamoDB table that the functions rely upon. This table holds the mock responses, the mock states, and the observations.

The step function also requires a topic to which to publish errors.

const testErrorTopic = new sns.Topic(this, 'TestErrorTopic');

testErrorTopic.addSubscription(

new snsSubs.LambdaSubscription(

this.observerFunctions[ResultCalculatorStateMachineTestStack.ErrorTopicObserverId]

)

);

Here we are wiring up an observer function to subscribe to the topic, so we can assert if error messages were published. The IntegrationTestStack exposes the generated observer functions via the observerFunctions property. This property is then be indexed by the observer id to obtain a reference to the function.

Finally we define the system under test, our state machine construct.

const sut = new ResultCalculatorStateMachine(

this,

ResultCalculatorStateMachineTestStack.StateMachineId,

{

fileHeaderReaderFunction:

this.mockFunctions[ResultCalculatorStateMachineTestStack.FileHeaderReaderMockId],

fileHeaderIndexReaderFunction:

this.mockFunctions[ResultCalculatorStateMachineTestStack.FileHeaderIndexReaderMockId],

combineHeadersFunction:

this.mockFunctions[ResultCalculatorStateMachineTestStack.CombineHeadersMockId],

calculateResultFunction:

this.observerFunctions[ResultCalculatorStateMachineTestStack.ResultCalculatorObserverId],

errorTopic: testErrorTopic,

}

);

this.addTestResourceTag(sut, ResultCalculatorStateMachineTestStack.StateMachineId);

As with observer functions, the IntegrationTestStack exposes mock functions via the mockFunctions property, indexed by the mock ids. Here we use this property to wire up the generated functions to the state machine. We also tag the state machine, so that we can interact with it in the unit tests.

The Unit Tests

For the unit test we will be using the Mocha testing framework and the Chai assertion library. The approach doesn't use anything specific to these, so it should be still viable if other frameworks and libraries are used.

As described in Part 3, we need to do create and initialise an instance of UnitTestClient before each test run. This instance will be used to interact with the cloud-based resources.

describe('FileEventPublisher Tests', () => {

const testClient = new UnitTestClient({

testResourceTagKey: ResultCalculatorStateMachineTestStack.ResourceTagKey,

});

before(async () => {

await testClient.initialiseClientAsync();

});

it('New scenario created', async () => {

// Our test goes here

});

});

Happy Path First

In this test, we want to ensure that the flow and mappings for the happy path are as expected. So first we specify the assertions and responses for the mock functions.

// Arrange

// .. snip test object creation...

await testClient.initialiseTestAsync({

testId: 'New scenario created',

mocks: {

[TestStack.FileHeaderReaderMockId]: [

{ assert: { requiredProperties: ['s3Key'] }, response: scenarioFileHeader },

],

[TestStack.FileHeaderIndexReaderMockId]: [

{

assert: { requiredProperties: ['fileType'] },

response: configurationFileHeaderIndexes,

},

],

[TestStack.CombineHeadersMockId]: [

{ assert: { requiredProperties: ['configurations'] }, response: combinedHeaders },

],

},

});

For each mock function, we have specified a set of assertions and responses. The assertions simply say that the event that triggers the mock function must contain the properties specified. If not, an error is thrown by the mock function. If the event matches, or if no assertion is specified, then the mock function returns the specified response.

For brevity, I have snipped the code that creates the

fileEvent,scenarioFileHeader,configurationFileHeaderIndexes, andcombinedHeaderstest objects. For those with a curious bent, you can find the full code for the tests here.

// Act

const sutClient = testClient.getStepFunctionClient(ResultCalculatorStateMachineTestStack.StateMachineId);

await sutClient.startExecutionAsync({ fileEvent });

The Act step is quite straightforward. We use the testClientinstance to get a step function client to interact with the system under test. We use StateMachineId defined on ResultCalculatorStateMachineTestStack to do this. We then call the client to start the step function with the test event.

We introduced the Await step in the last part of the series. This step is required in asynchronous event-driven testing, as things take time to work their way through queues, topics, streams and so forth. Here we wait until the step function state indicates that it has finished.

// Await

const { timedOut, outputs } = await testClient.pollOutputsAsync<ObserverOutput<any>>({

until: async () => sutClient.isExecutionFinishedAsync(),

intervalSeconds: 2,

timeoutSeconds: 12,

});

At this point in the code, the test has either timed out or the execution of the step function has finished. So, it is time to assert that things are as expected.

// Assert

expect(timedOut, 'Timed out').to.equal(false);

const status = await sutClient.getStatusAsync();

expect(status).to.equal('SUCCEEDED');

const resultCalculatorOutputs = outputs.filter(

(o) => o.observerId === TestStack.ResultCalculatorObserverId

);

expect(resultCalculatorOutputs.length).to.equal(configurationCount);

As well as the assertions that the test did not time out and that the step function succeeded, we also have an assertion that the ResultCalculator function was called the expected number of times. In fact, we could go even further here and inspect the content of the events that triggered the functions.

The Unhappy Paths

The first unhappy path that we consider caters for the scenario where the step function is incorrectly triggered. I.e., it is triggered by a change to neither a configuration nor a scenario file. In this case, we want to assert that the execution fails and that an error event is raised.

If we have our system configured correctly, then this makes testing this scenario at that level quite tricky as it should really never happen. However, as we are able to control the responses from our mock functions, then it becomes quite simple.

In the Arrange step of the test, we configure the mock function to return a file header with a file type of Result.

const unhandledFileHeader = { fileType: FileType.Result, name: `name:${nanoid()}` };

await testClient.initialiseTestAsync({

testId: 'Unhandled file type',

mocks: {

[TestStack.FileHeaderReaderMockId]: [{ response: unhandledFileHeader }],

},

});

Next we Act just as we did before.

const sutClient = testClient.getStepFunctionClient(ResultCalculatorStateMachineTestStack.StateMachineId);

await sutClient.startExecutionAsync({ fileEvent });

The Await step is where things are a little different. In addition to waiting for the step function to finish, we also wait until our error topic observer has outputted at least one event.

const getErrorOutputs = (outputs: ObserverOutput<any>[]): ObserverOutput<any>[] =>

outputs.filter((o) => o.observerId === TestStack.ErrorTopicObserverId);

const { outputs, timedOut } = await testClient.pollOutputsAsync<ObserverOutput<any>>({

until: async (o) => sutClient.isExecutionFinishedAsync() && getErrorOutputs(o).length > 0,

intervalSeconds: 2,

timeoutSeconds: 12,

});

Finally, we can assert that the test had the expected outcome.

expect(timedOut, 'Timed out').to.equal(false);

const status = await sutClient.getStatusAsync();

expect(status).to.equal('FAILED');

const lastEvent = await sutClient.getLastEventAsync();

expect(lastEvent).to.not.equal(undefined);

expect(lastEvent?.executionFailedEventDetails?.cause).to.equal('Unhandled FileType');

Here we are using the getLastEventAsync method to retrieve the last event emitted by the step function. With this, we can then assert that it contained the expected error cause. This gives us confidence that the flow is as we expect.

We can also assert that the expected error event was published.

const errorEventRecords = getErrorOutputs(outputs)

.map((o) => (o.event as SNSEvent).Records)

.reduce((all, r) => all.concat(r), []);

const errorEvent = JSON.parse(errorEventRecords[0].Sns.Message);

expect(errorEvent.error).to.equal('Unhandled FileType');

The other unhappy path to consider is when the first function errors when trying to read the input file header. To make matters more interesting, we have also configured the state to retry a couple of times.

This is where our mock functions again come to our aid. By specifying a value for error instead of response, we can instruct them to throw an error with the text specified.

await testClient.initialiseTestAsync({

testId: 'File reader retries and fails',

mocks: {

[TestStack.FileHeaderReaderMockId]: [

{ error: 'Test error 1' },

{ error: 'Test error 2' },

{ error: 'Test error 3' },

],

},

});

In this case, we don't supply any other mock responses, as we do not expect any other functions to be called.

The rest of the test is the same as the first unhappy path, until we get to the Assert.

expect(lastEvent).to.not.equal(undefined);

expect(lastEvent?.executionFailedEventDetails?.cause).to.equal('Failed to read the input file');

Here we assert that the failure is due to the expected cause.

Summary

In this post, I went through how it is possible to unit test the flow and mapping of step function by the use of mock and observer functions. I did gloss over how these are implemented, but if you are interested then the whole code can be found in the GitHub repo. My intention here was to explore the idea and show the possibilities of using CDK in this way.

It was interesting to develop a step function like this. I was decoupled from implementing the functions, I just concentrated on the contracts. I was able to deploy the step function and work on it interactively, amending the mappings and re-running the tests in the AWS console. I would then take the updated mappings, update the code definition, deploy the test stack and run the tests.

During this series of posts, I have ended up creating the start of what I hope will be an npm package that will enable anyone to start testing in this way. That is the intention, let us see if it comes to fruition. Happy testing!